Press

Why Pastured Eggs Are the Perfect Food

“Omne vivum ex ovo,” I notify my dining companion, scooping the last of a glorious plate of scrambled eggs from under her nose. It’s a grand pronouncement (“Every living thing comes from an egg”), but I’m in the mood for one. I love eggs, and we are living in an age of ovodolatry, of oeufphilia. It’s the Eggolith! These symbols of creation have, of course, been sacred for centuries. The Greeks had their Orphic egg, the Vedas their Cosmic egg. Enlightenment-era philosopher Denis Diderot famously pronounced that all the world’s theologies could be toppled by an egg! But here in America, for a tragic half century, eggs have been culinarily pedestrian—scrambled or fried at breakfast to the consistency of cardboard, tasteless yolks blending with bland whites. At last, something new is afoot.

It is not only that eggophiles stand in line for hours at Eggslut in L.A. And that New York’s Egg Shop does a brisk business in mezcal cocktails and dishes like the Warrior One—a poached egg, masala-spiced lentils, shaved broccoli. Or that the Japanese okonomiyaki—a cabbage omelet that can cure a hangover and most variations of malaise—has become ubiquitous. Or that Put an Egg on It is both a zine and a meme. It is that eggs are finally being coddled and cosseted, napped with fresh cream, crowned with caviar, festooned with the freshest offerings from the sea—all in ambitious testament to their culinary and cultural inviolability.

I first noticed this thrilling ascent late last winter at Fish & Game, a seasonal restaurant co-owned by Zak Pelaccio a convenient half block from my house in Hudson, New York. At one dinner, I ate a deep yellow–yolked, soft-cooked egg enthroned in a hollowed-out brioche with cultured cream, preserved lemon, and hackleback caviar; at another, a peekytoe-crab omelet with chile-crab sauce. A month later the same omelet—a barely puffy marigold duvet showered with tiny leaves of baby celery, cilantro, borage flowers, and frizzled leeks—arrived with an entire soft-shelled crab astride. There was Italian torrone—made with egg whites, almonds, and sugar—for dessert. Where else, I wondered, were eggs being thus glorified?

It was time for some fieldwork. “ ’Tis hatched, and shall be so!” I announced, from Shakespeare, entering Frenchette, Riad Nasr and Lee Hanson’s new Tribeca bistro, where the brouillade, a prodigiously rich rendition of a soft French scramble that is luxurious in the extreme, has gained immediate renown. What arrives when one orders it—a downy bed of daffodil yellow on a Frisbee-size plate with a swirl of herby, buttery snails at its center—would be called “scrambled” only by a philistine. It costs $22 and is worth every cent.

The pungent snails contribute considerably to the pleasure of the brouillade. As does the ratio of butter to eggs: a generous 40 grams (about three tablespoons) per two eggs. Nasr bashfully admits that this is about 1:2 by weight.

But why the bashfulness? Fat, as all sentient beings know, is delicious, and it has a unique, scientifically proven ability to carry flavor. Eggs have a unique affinity for fat, which seems singularly able to elaborate their innate subtle richness.

Recent nutritional research has shown that we must no longer fear becoming fat from eating fat. I have a July 19 Atlantic article titled “The Vindication of Cheese, Butter, and Full-Fat Milk” tacked above my desk, beside a Washington Times article explaining that saturated fats neither clog arteries nor cause heart disease. Last year, The Lancet reported an observational study of nearly 135,000 people demonstrating that those who ate the least saturated fat had higher rates of heart disease and early mortality; those who ate the most had the fewest strokes.

I celebrate these discoveries at Flora Bar in the Met Breuer, where, for $32, I’m served an exquisite omelet topped with trout roe, a lump of hackleback caviar, and a smudge of crème fraîche. The eggs themselves—two, mixed with a touch of salt and steamed in butter—resemble an almost paper-thin crepe. It is the sort of dish one imagines a meditation teacher advising you to eat mindfully, and I eat it in very small bites, chewing each 150 times. Next time I may order two. Chef Ignacio Mattos tells me that the omelet’s delicacy is intentional. “The idea was to make it as delicate and different from heavy and filling egg dishes as it could be.”

So far the results of my egg inquiry could be distilled as (1) fat, (2) caviar. But what about other basic egg questions? For example: When did we start eating eggs? A long time ago. Ancient Romans ate peafowl eggs. Phoenicians ate ostrich eggs. In the Faroe Islands off the coast of Iceland, eggs of the fulmar—a white seabird—are traditionally collected by tying oneself by woolen harness to the top of a sheer cliff, descending to narrow ledges, and then being hauled back up by fellow climbers (or an ATV). Chicken eggs are much simpler to get, requiring no harnesses or belay equipment, and have likely been part of the human diet since about 1400 b.c., if not earlier.

Do fresh eggs have to be refrigerated? Only if they have been washed! This rids them of feathers and less-mentionables but also of a protective coating that keeps them safe and sound and bacterially immune on the countertop. How long do eggs last? Three to five weeks—or a year, frozen (!). How do you boil an egg? It is my opinion that one should not boil it: Put eggs into a pot of water, bring the water to a boil, turn off the heat, and leave the pot, covered, for five minutes. How do you poach an egg? Crack it into a ramekin, drop it into just-simmering water with a little vinegar in it, check for doneness by poking it with a slotted spoon. Are eggs good for you? The answer is: It depends. For millennia, eggs were laid by chickens that pecked and foraged. Then, beginning around the middle of the last century, chickens were confined to battery cages and bred to lay twice as many eggs as they used to. This arrangement yielded worse eggs—not only tasteless but high in cholesterol and lower in vitamins.

But the eggs being served at Frenchette, Flora Bar, and other portents of the Age of Egg are pastured eggs: eggs from chickens that still forage and peck and lay less frequently. Such eggs, which are reliably for sale at farmers’ markets—and at supermarkets; look for Vital Farms—are very healthy, low in cholesterol, high in vitamins A and E and carotene, with triple the omega-3s of the average supermarket egg, and the exact dietarily recommended ratio of omega-3s to omega-6s. The final variable to consider is the breed of the laying hen. Chef Dan Barber, of Blue Hill at Stone Barns, tells me that older-breed chickens both are better at foraging and lay fewer eggs, which are richer and more concentrated. “There’s a Venn diagram waiting to be created where the breed and diet meet for the perfect egg,” Dan tells me.

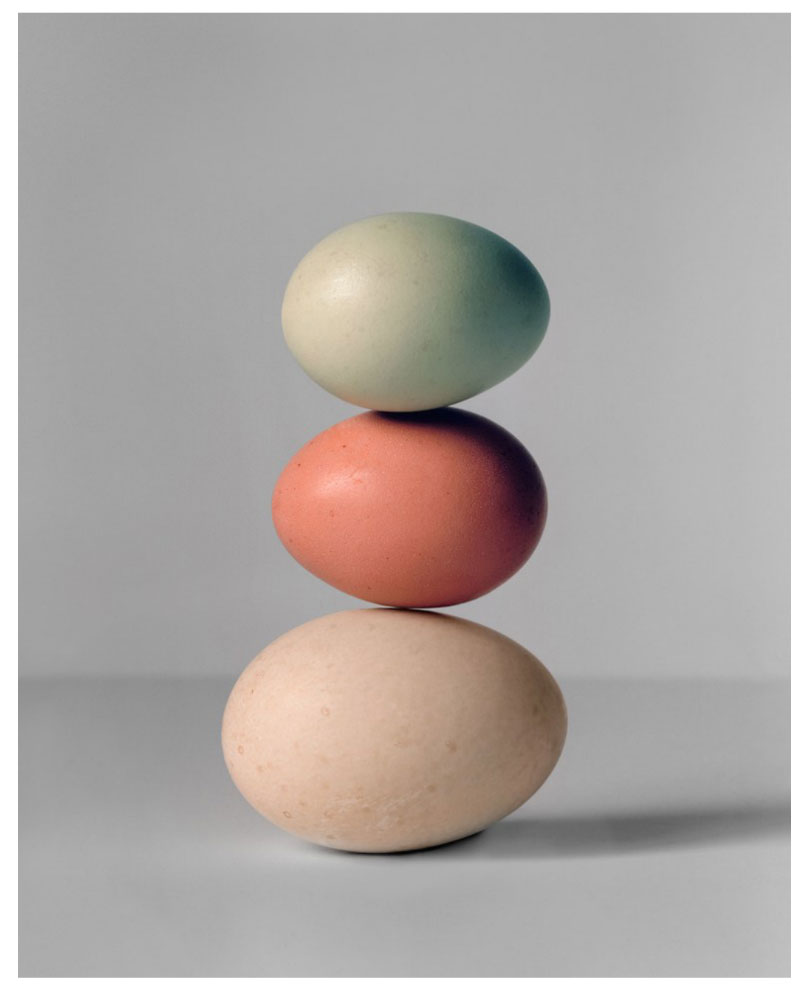

The perfect egg! I must find it. On a sweltering morning, I take a short drive to Red Hook, New York, and arrive at Yellow Bell, the Platonic ideal of a chicken farm. The barns are deep red. Fields full of clover, wood sorrel, alfalfa, and grass undulate in the dappled light. Owner and farmer Katie Bogdanffy greets me in jeans, boots, and bright-red lipstick, impressively resilient under the day’s substantial heat. “Delawares are particularly good foragers,” she tells me. “They lay a beautiful cream-colored egg.” She introduces me to Barred Rocks, Ameraucanas, Cuckoo Marrans, Golden Comets, Whiting True Blues. I clamber into their coops, which smell fresh and grassy and are moved every few days by tractor to a new area of pasture. The birds are clean and happy. Life is good.

Bogdanffy sends me home with two dozen eggs in a rainbow array of hues and sizes. They are not only handsome but deep golden and creamy of yolk, with whites that cohere with admirable robustness when cracked into a waiting pan.

I decide that an imitation of Riad Nasr and Lee Hanson’s brouillade is the way to go. They add cream, which I don’t have, and I’d forgotten to ask them what size pan. But I watch a video of the actor Ian McKellen cooking “the best scrambled eggs in the world” in a saucepan at the Chateau Marmont, and copy him. Things go swimmingly until I’m sitting down to eat. The butter, which makes up a third of the content of the bowl, begins to seep unpleasantly from the eggs. I write Harold McGee, an expert in egg-fat science. “The butter seepage probably has to do with how you incorporated it into the eggs. I think the best way to ensure against that would be to melt the butter and whisk it into eggs that are warm enough that they won’t congeal the fat as it hits. That should emulsify it evenly and provide each droplet with maximal eggsulation against pooling together.” I read this carefully several times, then close my computer.

I direct my attention to my remaining eggs and decide just to make them as I like them: boiled, halved, salted, and lightly adorned with something salty and rich. I happen to have the dried, salted fish roe bottarga on hand, and a single anchovy dug from a special jar smuggled to me by Ligurian friends last spring. I mix a bit of fresh summer garlic, pounded to a paste with the end of my mayonnaise. I choose three lovely eggs: one blue, one deep brown, and one creamy Delaware egg, and I manage to boil, crack, and peel them without mishaps. I halve each, sprinkle their yolks with flaky salt, and bestow each with its own garnish. The perfect egg needs nothing more, it turns out, than careful attention. The rest it can do on its own.